Tatiana

Staying here, in Russia, is suicidal

I am 44 years old, an art historian by profession. I was born and raised in the Tver province. I received my education there as well. I worked as a designer in Moscow for a few years and then moved to the south of Russia. I have two sons, aged 24 and 6.

Like many Soviet children, I had a very ordinary life, just like everyone else. My father was a teacher, my mother a doctor. There were moments when my parents fought for their rights, but I only fully realised that once I grew up. It was then that I understood that the government couldn’t care less about its citizens: a human life does not hold value in Russia.

Of course, there are many magnificent things in Russia: nature, ancient cities with cultural monuments. But in order to understand people’s attitudes towards these things, it’s enough to go on a trip…just a week ago, I was driving through the Voronezh region with its beautiful oak and pine groves and was horrified by the garbage dumps along the side of the roads. When I arrived in my hometown, I saw that instead of the solid, beautiful old house, which had stood in its rightful place back in February, yet another “ant-hill” [high rise apartment building] was being built. In Moscow, they’re renovating a historical building, knocking down the stunning glazed Art Nouveau tiles and replacing them with a pathetic imitation…it feels like a system of destruction and annihilation has been turned on.

I am kept in Russia only by people — my elderly mother and eldest son, whose future I worry about under the current circumstances. In our family, we have an unambiguous attitude towards what’s happening — this is war, and whatever words can be used for these events, it doesn’t change the meaning. After the first conversations with friends (I have quite a few), I realised that I wasn’t able to discuss this topic. I get angry and lash out. Because in my head I can’t understand how it’s possible to justify the slaughter of people, how it’s possible to annihilate cities. How is it possible in the 21st century, after everything that we’ve lived through, to go and attack your own neighbour…

How the Ukraine war is creating family rifts in Russia

Some of my relatives also support the actions of the government, which is why at the moment we don’t communicate that much so as not to inflame the atmosphere. My arguments and attempts to open their eyes are like talking to a brick wall. At work and everywhere else, I feel like the majority think that what is happening is right. There are people who share my point of view, but we are few…and when you meet such a person, you celebrate them like a ray of light in the darkness. I can only calmly speak about this topic with my husband and children. But in reality, I am alone.

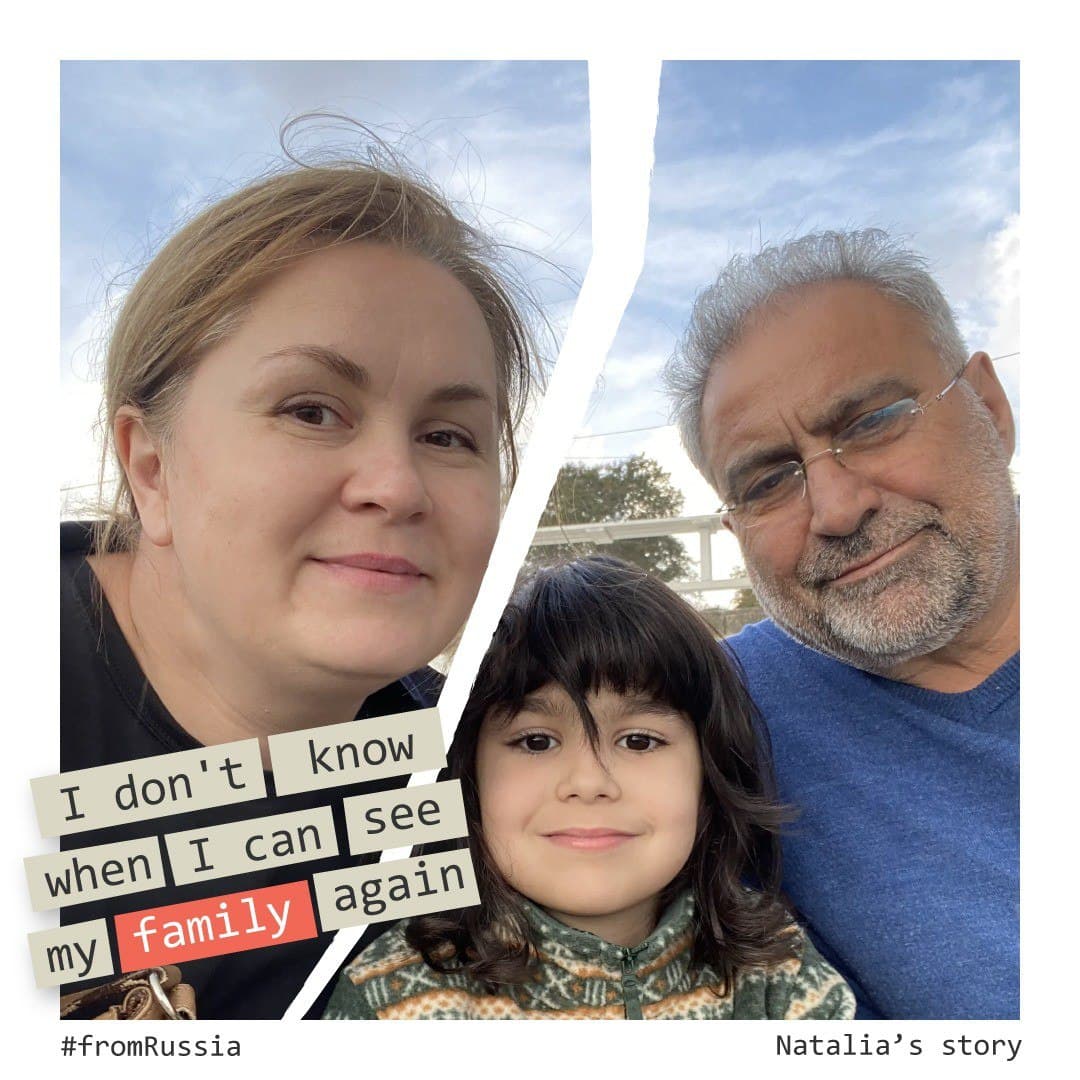

I don’t really want to speak about material things, but everything that had been earned through honest labor is now stuck for obvious reasons and it’s unknown what will happen next. All these events have pushed me to have my youngest child leave Russia. He and my husband (though, truthfully, we aren’t married) left for the Czech Republic. Because they had permanent residency, they had the opportunity. Before there were relocations back and forth, and we couldn’t make a final decision [about where to live]. However, all the events that started to happen with the outbreak of the war left us with one decision — to leave.

Unfortunately, I am staying in Russia because my three-year visa expired during the pandemic and the new visa, which I applied for shortly before the start of the war, was denied. The consequence is that we don’t know when we will see each other again. It’s terrifying that the borders might be closed and we will find ourselves behind a new “iron curtain.”

Everyone around continues living their normal lives, as if nothing is happening. It’s a bit eerie to me. On top of that, I have to share my worries less with people. And, essentially, I have no one to share them with.

The only problem right now is the absolute uncertainty of when I might be able to see my family in person. My husband is 67 years old; my child is six. We may not have much time to be together. I am concerned about his health because he worries a lot about this situation, but like all men, he tries to keep everything on the inside. We don’t talk about bringing our child back to Russia.

I would like to try to push for getting a visa to the Czech Republic to see my son and husband. If it is again going to be impossible, then I will probably have to try to obtain a visa from another Schengen country. I want to write a letter to Jan Lipavský (Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic) and the Czech consul general in Moscow. Then we’ll take it from there. We have to help our kid adapt to school.

Of course, I would like for the process of issuing visas and permanent residencies to not be delayed because of nationality. Separating parents from children indefinitely does not seem quite right to me. I understand that everyone wants to punish Russians now, but why punish little children? Many parents send their children abroad precisely so that they can live in a free democratic society, in which a person’s life in and of itself has importance, not because of what skin color they have or where they come from. I nonetheless hold out hope that, for such situations, some changes will be made in our favour.

Dieser Artikel wurde noch nicht ins Deutsche übersetzt. Wir suchen nach Freiwilligen, die uns dabei helfen können.

Staying here, in Russia, is suicidal

...No one could ever imagine that literally tomorrow you would have to turn your life around 180 degrees and leave for a foreign country.

...Gebt nicht auf und verzweifelt nicht, tut, was ihr für richtig haltet. Russland wird auf jeden Fall frei sein.

Unsere Medienplattform würde ohne unser internationales Freiwilligenteam nicht existieren. Möchten Sie eine_r davon werden? Hier ist die Liste der derzeit offenen Stellen:

Gibt es eine andere Art wie Sie uns unterstützen möchten? Lassen Sie es uns wissen:

Wir berichten über die aktuellen Probleme Russlands und seiner Menschen, die sich gegen den Krieg und für die Demokratie einsetzen. Wir bemühen uns, unsere Inhalte für das europäische Publikum so zugänglich wie möglich zu machen.

Möchten Sie an den Inhalten von Russen gegen den Krieg mitwirken?

Wir wollen die Menschen aus Russland, die für Frieden und Demokratie stehen, gehört werden lassen. Wir veröffentlichen ihre Geschichten und interviewen sie im Projekt Fragen Sie einen Russen.

Sind Sie eine Person aus Russland oder kennen Sie jemanden, der seine Geschichte erzählen möchte? Bitte kontaktieren Sie uns. Ihre Erfahrungen werden den Menschen helfen zu verstehen, wie Russland funktioniert.

Wir können Ihre Erfahrungen anonym veröffentlichen.

Unser Projekt wird von internationalen Freiwilligen betrieben - kein einziges Mitglied des Teams wird in jeglicher Weise bezahlt. Das Projekt hat jedoch laufende Kosten: Hosting, Domains, Abonnements für kostenpflichtige Online-Dienste (wie Midjourney oder Fillout.com) und Werbung.

Russland hat den Krieg gegen die Ukraine angefangen. Dieser Krieg dauert schon seit 2014 an. Er hat sich seit 24. Februar 2022 nur noch verschärft. Millionen von Ukrainern leiden. Die Schuldigen müssen für ihre Verbrechen zur Rechenschaft gezogen werden.

Das russische Regime versucht, die liberalen Stimmen zum Schweigen zu bringen. Es gibt russische Menschen, die gegen den Krieg sind - und das russische Regime versucht alles, um sie zum Schweigen zu bringen. Wir wollen das verhindern und ihren Stimmen Gehör verschaffen.

**Die russischen liberalen Initiativen sind für die europäische Öffentlichkeit bisweilen schwer zu verstehen. Der rechtliche, soziale und historische Kontext in Russland ist nicht immer klar. Wir wollen Informationen austauschen, Brücken bauen und das liberale Russland mit dem Westen verbinden.

Wir glauben an den Dialog, nicht an die Isolation. Die oppositionellen Kräfte in Russland werden ohne die Unterstützung der demokratischen Welt nichts verändern können. Wir glauben auch, dass der Dialog in beide Richtungen gehen sollte.

Die Wahl liegt bei Ihnen. Wir verstehen die Wut über die Verbrechen Russlands. Es liegt an Ihnen, ob Sie auf das russische Volk hören wollen, das sich dagegen wehrt.