How All of Russian TV Became State-Controlled

Short biography of the freedom that never happened.

Since the beginning of the war, many have been interested in the question whether or not most Russians support the military aggression in Ukraine and the government actions in general. Despite the ongoing opinion polls, there may be no simple answer to this question — because of the way social research functions in authoritarian contexts that casts doubt on whether polls published in Russia can be trusted.

Polling in Russia, as well as social and political research organisations in general, have increasingly been under government control in recent decades. Social and political sciences experienced increased political pressure as the more liberal universities, such as the European University in Saint Petersburg and the Moscow School for the Social and Economic Sciences, were denied accreditation; political scientists from Moscow Higher School of Economics and MGIMO and faculty members from the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences of the St. Petersburg State University were fired. Between 2014 and 2016, among others, the Centre for Independent Social Research in Saint Petersburg, the Center for Social Policy and Gender Studies in Saratov, and the Levada Center in Moscow (one of the biggest polling organisations in Russia) were labelled as “foreign agents”, as a result of which the second was closed, and the third lost the ability to publish its results in all major Russian media — not to mention the fact that this status made research itself difficult. This means that today’s polling and social research landscape in Russia is dominated by VCIOM (Russian Public Opinion Research Center) and FOM (Public Opinion Foundation), for both of which the government (for FOM specifically — the Presidential Administration) is the main source of funding and the main client.

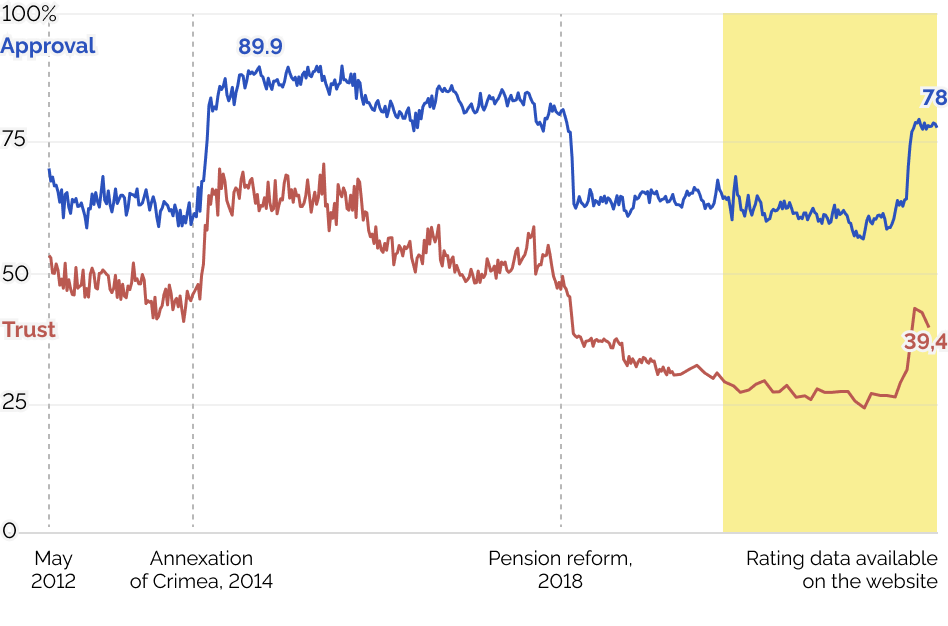

The organisations controlled by the government can deliver the poll results suited to the client’s needs. This does not necessarily mean outright falsifications (the answers to the same questions obtained by the loyal VCIOM and the “foreign agent” Levada Center do not differ by much). However, what can be manipulated is which topics are addressed or not addressed at all, how the questions are framed, which options are given to the responders, and which results are published. Changing just one of these parameters can completely alter the poll’s results. For example, in 2019, VCIOM’s rating of President Putin (based on an open-ended question) had fallen to 30,5%. To remedy the situation, VCIOM changed the question wording, making it a closed question, which brought Putin’s rating back to 72,3%. Another example — VCIOM regularly asks respondents questions about Navalny but almost never publishes the results.

Actual approval rating. Source: proekt.media

When it comes to surveys related to the war, the pollsters use the government-approved framing of it as “special military operation”. It is likely that, if the words “war” or “Russia’s attack on Ukraine” were used, the numbers of its supporters in the poll would be different. In the Russian official media, the overall numbers of support for the “military operation” are cited — but not the fact that, according to the polls, this support is minimal among young people under 30.

In this sense, public opinion polls are used as a tool for propaganda, to create the impression of overwhelming support and legitimise the government’s actions. This effect has been termed the “Spiral of silence” by Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann (a post-WW2 German political scientist): seeing the majority supporting something, the previously undecided join the majority to avoid being outcasts, and those who find themselves in the minority are demotivated to speak up; because of this, next time, the majority is even bigger, and the pressure to join it is even stronger, making even more people express support — and so on. This effect is especially relevant for authoritarian countries.

Even when the surveys are not manipulated, in authoritarian contexts the answers are distorted by the subject of the study — the population itself, due to self-selection of those who decide to participate as opposed to those who refuse. There is a reason to believe that, when simply saying something wrong publicly can lead to 15 years in prison, people (especially those who oppose the official point of view) might not want to answer questions posed by strangers. According to a 2020 survey by Levada Center, in Russia supporters of the regime more often trust opinion polls than opponents of the regime do (58% vs. 32%), which may lead to overrepresentation of supporters. The Russian Field researcher group and Maxim Kats conducted a survey to ask people what they think about war, and 29,400 people out of 31,000 refused to speak to the interviewers.

Of those who agree to the interview, not all may give their true opinion. They may exaggerate their support out of fear of persecution or out of the wish to be with the majority and give a socially desirable answer (the social desirability bias can be present in all societies but mass preference falsification is very characteristic for authoritarian regimes). Sociologists Chapkovski and Schaub in their study show more than 10% of Russians that are afraid to speak frankly about the war in a survey. During war times, people may answer under the influence of very strong but fluctuating emotions, and give more radical answers (both in support and opposition) than they otherwise would. Most importantly, in order to have an opinion, one must have an opinion, and a big proportion of people in Russia (as in many authoritarian regimes) are alienated from politics, they believe that nothing depends on them and therefore see little point in forming an opinion, especially under the influence of propaganda that leads them to believe that “we don’t know all the truth” and “everybody lies”. Finally, when people express support, it does not necessarily tell us much about what exactly people are supporting, how they interpret the question posed by the pollster.

One of the main features of authoritarianism is the lack of feedback from society to the political system. Since the people do not have the freedom to express their will, its true opinions remain a black box that may contain something different than what is on the surface. For example, in communist countries, open opposition to the regime was very low until its very fall.

However, it may also be that the high support of the government shown by the pollsters is simply due to the rally ‘round the flag effect when the society consolidates around leaders during war times as they perceive themselves to be surrounded by enemies.

The fact is that we simply do not know what is in the black box, and we do not have a reliable way to find out.

However, it does not mean that polls are completely meaningless. If one knows about their limits, there is still something to be learned — for example, how opinions vary between different age groups. And while we cannot be sure about quantitative results (the numbers of supporters and opposition), studies based on other methods, such as deep interviews and focus groups, do at least give some information about different types of motivation for support or lack thereof. Finally, the surveys that are less obviously political (e.g. about values that underlie the official ideology) may give more accurate results because people are less afraid to respond openly.

Dieser Artikel wurde noch nicht ins Deutsche übersetzt. Wir suchen nach Freiwilligen, die uns dabei helfen können.

Short biography of the freedom that never happened.

In part 1 we've covered the state position to economy. What is the stand of the public?

Conspiracy theories and bogus science: Russia uses this in criminal cases, propaganda and justification of war. What are the most famous cases of this and how does it work?

Unsere Medienplattform würde ohne unser internationales Freiwilligenteam nicht existieren. Möchten Sie eine_r davon werden? Hier ist die Liste der derzeit offenen Stellen:

Gibt es eine andere Art wie Sie uns unterstützen möchten? Lassen Sie es uns wissen:

Wir berichten über die aktuellen Probleme Russlands und seiner Menschen, die sich gegen den Krieg und für die Demokratie einsetzen. Wir bemühen uns, unsere Inhalte für das europäische Publikum so zugänglich wie möglich zu machen.

Möchten Sie an den Inhalten von Russen gegen den Krieg mitwirken?

Wir wollen die Menschen aus Russland, die für Frieden und Demokratie stehen, gehört werden lassen. Wir veröffentlichen ihre Geschichten und interviewen sie im Projekt Fragen Sie einen Russen.

Sind Sie eine Person aus Russland oder kennen Sie jemanden, der seine Geschichte erzählen möchte? Bitte kontaktieren Sie uns. Ihre Erfahrungen werden den Menschen helfen zu verstehen, wie Russland funktioniert.

Wir können Ihre Erfahrungen anonym veröffentlichen.

Unser Projekt wird von internationalen Freiwilligen betrieben - kein einziges Mitglied des Teams wird in jeglicher Weise bezahlt. Das Projekt hat jedoch laufende Kosten: Hosting, Domains, Abonnements für kostenpflichtige Online-Dienste (wie Midjourney oder Fillout.com) und Werbung.

Russland hat den Krieg gegen die Ukraine angefangen. Dieser Krieg dauert schon seit 2014 an. Er hat sich seit 24. Februar 2022 nur noch verschärft. Millionen von Ukrainern leiden. Die Schuldigen müssen für ihre Verbrechen zur Rechenschaft gezogen werden.

Das russische Regime versucht, die liberalen Stimmen zum Schweigen zu bringen. Es gibt russische Menschen, die gegen den Krieg sind - und das russische Regime versucht alles, um sie zum Schweigen zu bringen. Wir wollen das verhindern und ihren Stimmen Gehör verschaffen.

**Die russischen liberalen Initiativen sind für die europäische Öffentlichkeit bisweilen schwer zu verstehen. Der rechtliche, soziale und historische Kontext in Russland ist nicht immer klar. Wir wollen Informationen austauschen, Brücken bauen und das liberale Russland mit dem Westen verbinden.

Wir glauben an den Dialog, nicht an die Isolation. Die oppositionellen Kräfte in Russland werden ohne die Unterstützung der demokratischen Welt nichts verändern können. Wir glauben auch, dass der Dialog in beide Richtungen gehen sollte.

Die Wahl liegt bei Ihnen. Wir verstehen die Wut über die Verbrechen Russlands. Es liegt an Ihnen, ob Sie auf das russische Volk hören wollen, das sich dagegen wehrt.