How All of Russian TV Became State-Controlled

Short biography of the freedom that never happened.

In modern times, a feminist punk rock group Pussy Riot gained international attention for their provocative protests against the Russian government. Members of the group faced arrest and imprisonment for their bold performances, which criticised Vladimir Putin and his administration. Their defiance in the face of censorship and repression captured the imagination of activists worldwide, sparking discussions about the importance of artistic freedom and political dissent.

Rehearsal of punk band Pussy Riot, photo by Denis Bochkarev

By standing in solidarity with cultural dissidents like Zamyatin, Pussy Riot, and many others, we reaffirm our commitment to defending human rights and democratic principles on the global stage. We recognize that the struggle for freedom in Russia is not isolated but part of a broader fight for justice and equality worldwide. Supporting dissidents sends a powerful message to authoritarian regimes that violations of human rights will not be tolerated or ignored.

The cultural dissident movement in Russia serves as a vital barometer of the country's political climate and the resilience of its civil society. Despite facing significant risks, dissidents continue to speak out against government repression and corruption, inspiring others to join the fight for change. Their bravery serves as a source of hope and inspiration for those who believe in a future where democracy and human rights prevail.

When discussing current Russian dissident culture, it is important to start with its historical roots. Except for the 90s, when there was some space for critical voices, Russia as well as the Soviet Union have a long history of authoritarian and totalitarian systems. Because of this experience, the development of contemporary Russian dissident culture varies from opposition coming from democratic contexts. Understanding the nuances of Russian and Soviet dissident culture helps to shed light on Russian dissident culture and its dynamics. We’ll start with the rise of the Soviet totalitarian regime, how dissent was controlled and the forms it took.

Among the earliest instances of dissent was the "Philosophers' ships" affair in the 1920s, where more than 200 prominent intellectuals critical of the regime were exiled abroad. As Leslie Chamberlain notes in her seminal book about this event, Lenin’s Private War: The Voyage of the Philosophy Steamer and the Exile of the Intelligentsia, the only “crime” any of the deportees had committed was to refuse to let go of their closely held beliefs.

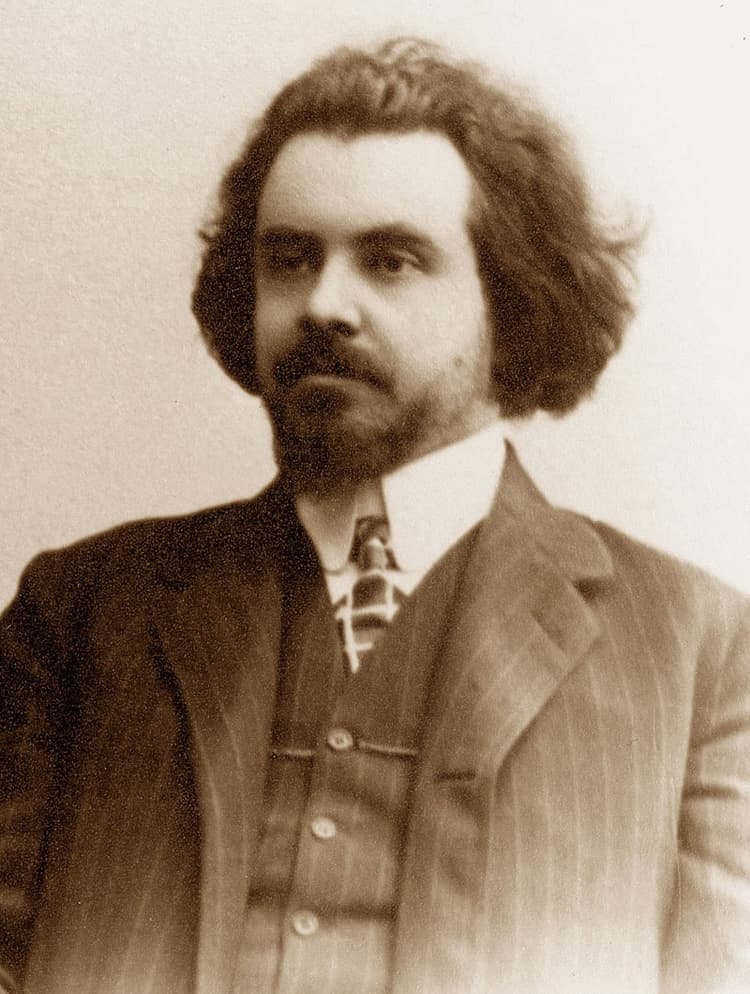

Nikolai Berdyaev, exiled philosopher of mystic non-Orthodox Christianity

As an example, Nikolai Berdyaev, a renowned philosopher of mystic non-Orthodox Christianity and critical philosophy, openly expressed his opposition to communism during interrogations:

“Any class organisation or party should be subordinated to the individual and to humanity… no party past or present arouses any sympathy in me.”

Nikolai Berdyaev

Refusing to confess guilt, he signed a pledge not to return to Russia without permission and left for Germany. Berdiaev passed away in Paris in 1948, leaving behind a legacy as a world-renowned philosopher and historian.

Among the exiled were philosophers:

Others were great historians:

The exiled sociologist Pitirim Sorokin later gained world recognition and became one of the founders of American sociology. Some dissidents were able to continue their intellectual careers in Europe. Others were not so lucky, falling into poverty and destitution.

As the Soviet Union transitioned from Lenin's rule to the Stalinist era, political repression intensified. Joseph Stalin's regime implemented widespread purges and the establishment of labour camps (Gulags) to suppress dissent and maintain control over society. The state exercised strict control over all forms of media, literature, and art, promoting Socialist Realism as the only acceptable artistic style and ideology. Socialist Realism echoed the values of the state, presenting an idealised version of a Socialist present and future. Artists and writers in particular, who not only criticised these values but did not adhere to the style of Socialist Realism, were considered dissidents and threats to the state.

Arlen Blum characterises this phase in the evolution of Soviet censorship as the "era of total terror," while Gennady Zhirkov refers to it as the era of "total party censorship." During this time, a thorough censorship system emerged, spanning from self-regulation among individuals to stringent party oversight of control.

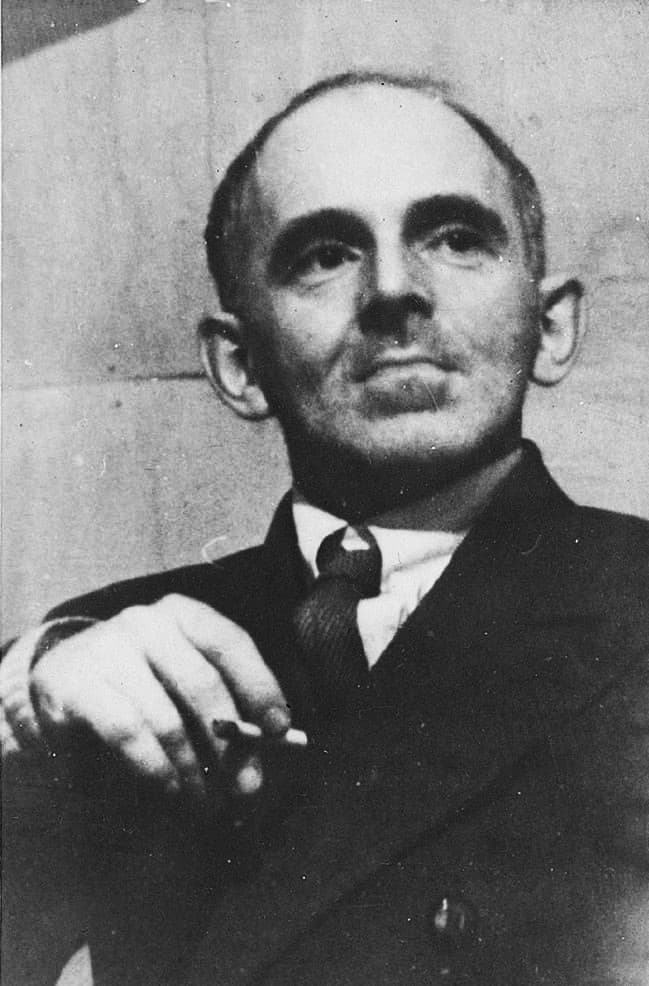

Osip Mandelstam, author of the poem Stalin Epigram

Among those who were persecuted are the classics of Russian literature, as they are considered today. For instance, Osip Mandelstam, the poet, was arrested for the first time in 1934 and, together with his wife, was sent into exile near Perm, a smaller Russian city. At that time, this was a rather mild punishment for writing and reading the "Stalin Epigram", which he recited at a few small private gatherings in Moscow. The poem deliberately insulted Stalin:

His thick fingers are bulky and fat like live-baits,

Osip Mandelstam's poem 'Stalin Epigram'

And his accurate words are as heavy as weights.

Cucaracha’s moustaches are screaming,

And his boot-tops are shining and gleaming.

Osip's freedom was short-lived. He was rearrested in 1938 and sent to the Far East. On December 27, 1938, the poet died of typhus in a transit prison, with his final resting place still unknown.

Marina Tsvetaeva, author of the poem And God be with you!

Marina Tsvetaeva, the poetess, lived through the Bolshevik Revolution and the Russian Civil War: experiencing famine, poverty, immigration, and Stalinist repression.

And God be with you!

Marina Tsvetaeva, poem 'And God be with you!'

Be — sheep!

Go in flocks, flocks

without dreams, without thoughts of your own

after Hitler or Stalin

Display on your sprawled bodies

star or Swastika hooks.

In 1939, upon returning to Moscow with her son from France, Tsvetaeva encountered closed doors at every turn. Despite picking up occasional translation work, established Soviet writers turned a blind eye to her struggles and refused to assist her. Meanwhile, her husband was sentenced to death and her daughter Alya endured over eight years of imprisonment. In 1941, amidst the chaos of war, Tsvetaeva and her son were evacuated to Yelabuga (Elabuga), where she found herself without any means of support. Tragically, on August 31, 1941, Tsvetaeva took her own life.

The poet and translator Nikolai Zabolotsky was tortured and accused of taking part in a counter-revolutionary plot with other Leningrad (St Petersburg) writers and was sentenced to five years in 1938. However, after the camps, he was also sent into exile on Far Eastern construction sites.

With the death of Stalin in 1953, the terror ended in the Soviet Union, and the state’s relationship to and control of cultural dissidents changed.

Between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s, Nikita Khrushchev's policies of de-Stalinization and peaceful coexistence with other nations lightened repression and censorship in the Soviet Union. Consequently, dissent began to emerge in the country. During this period, literature, especially fiction, played a pivotal role as the primary source of cultural dissent, significantly influencing citizens and shaping their protest-oriented worldview and actions.

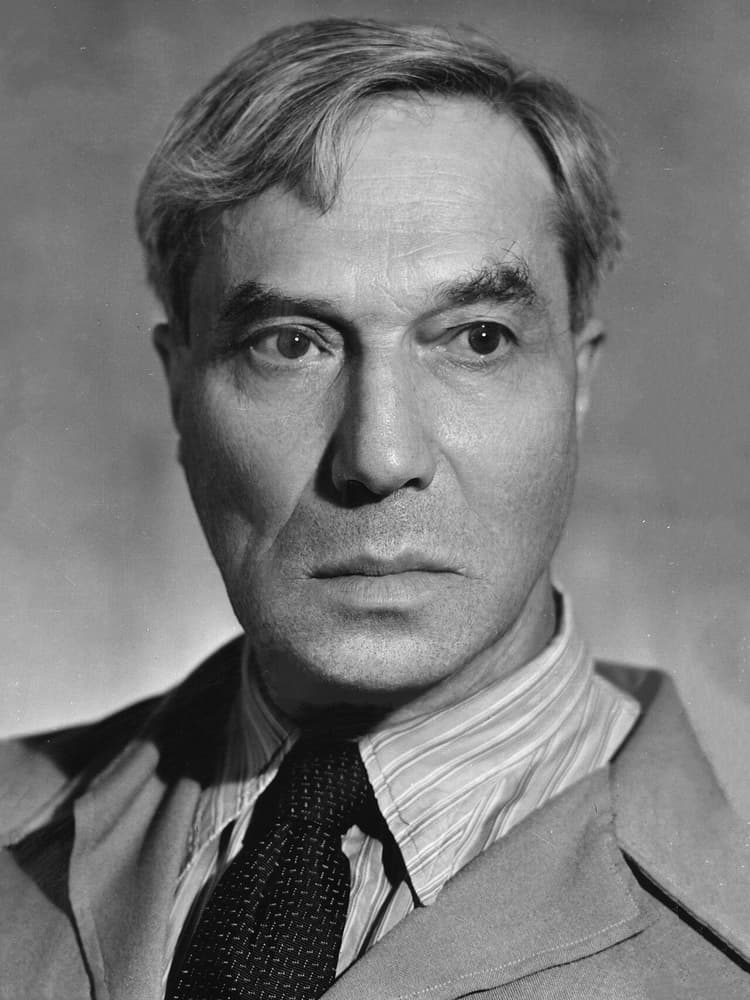

Boris Pasternak, author of the novel Doctor Zhivago

In 1958, Khrushchev launched a vigorous assault on Boris Pasternak following the publication of his novel Doctor Zhivago abroad, which had been banned from publication in the Soviet Union. Doctor Zhivago follows the protagonist from 1902 until the Stalinist Era, presenting critiques of the Soviet Era. Soviet censors interpreted certain passages as anti-Soviet and objected to Pasternak's subtle critiques of Stalinism, Collectivization, the Great Purge, and the Gulag.The rejection of Pasternak's novel by state editors stemmed from its departure from Socialist Realism, with the author demonstrating a greater concern for individual welfare over societal welfare. "Pravda," the main Party newspaper, disparaged the novel as "low-grade reactionary hackwork," leading to Pasternak's expulsion from the Writer's Union. Although Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, he faced intense domestic pressure and ultimately declined it. Khrushchev ordered a cessation of attacks on Pasternak once he refused the prize.

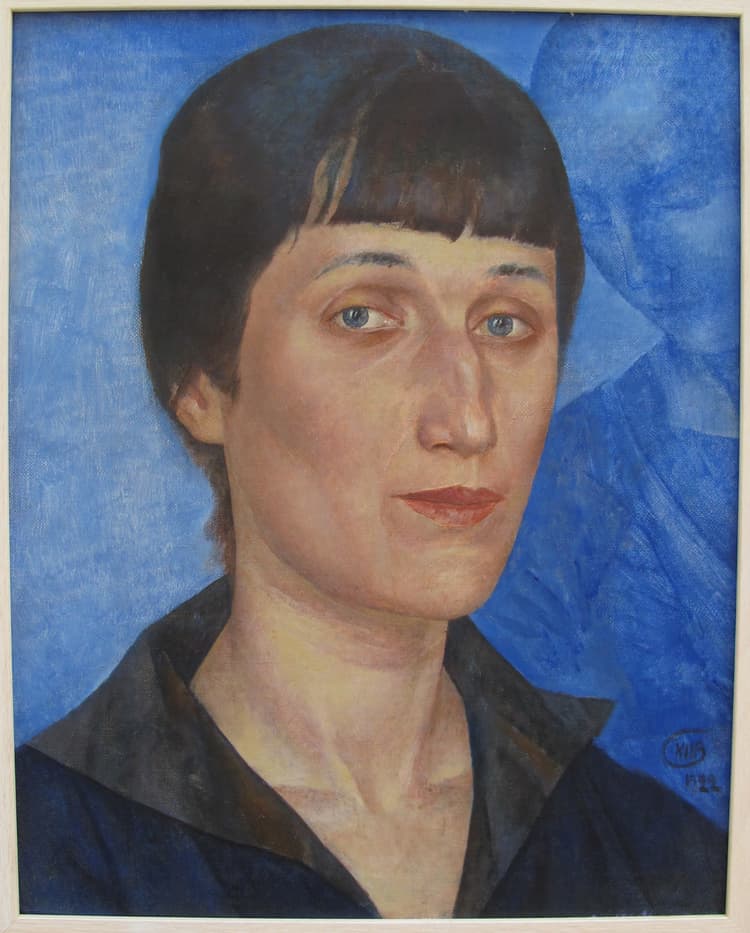

Anna Akhmatova, author of the poem Requiem

Renowned poet Anna Akhmatova similarly published a more critical poem after the death of Stalin. “Requiem” is about how people suffered during the Great Purge. It was written over three decades, between 1935 and 1961. Akhmatova feared that it would be too dangerous for herself and those around her if she released the poem during the 1940s when it was written. It was not until the death of Stalin that she finally decided that it was the right time to publish it. The work in Russian finally appeared as a book in Munich in 1963; the whole work was not published within the USSR until 1987. It would become the best-known work of poetry about the Soviet Great Terror.

Seventeen months I've pleaded

from Requiem. Trans. A.S. Kline, 2005

for you to come home.

Flung myself at the hangman's feet.

My terror, oh my son.

And I can't understand.

Now all's eternal confusion.

Who's beast, and who's man?

How long till execution?

At the end of the 1950s in Russia, a new trend appeared in art. Most often this art is called "non-official" or "non-conformist", emphasising its fundamental difference from official Socialist Realism.

The aim of Non-Conformism was to challenge and question the legitimacy of the official artistic byline, often employing irony in the process. Numerous groups and movements emerged in the USSR during this era, such as the:

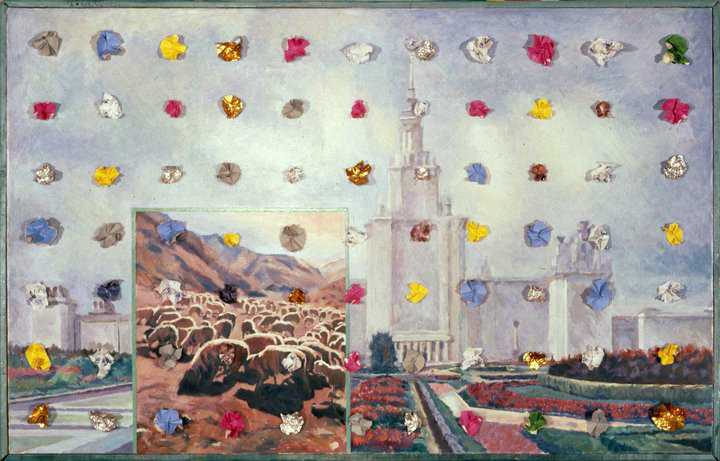

Ilya Kabakov Holiday #1

Among the many deserving artists, notable figures include:

Sidur's monument Treblinka, Berlin

The artists were primarily drawn to the freedom of expressing their personal Weltanschauung, their subjective worldview, free from external influences such as politics and ideology. Their focus revolved around intimate genre paintings featuring unconventional characters brimming with expressive individuality, as seen in the works of Vadim Sidur and Ernst Neizvestny. Rather than adhering to a "historic truth," they embraced a "subjective truth," exploring and interpreting various facets of reality that touched upon existential concerns of both the individual and humanity.

This thematic shift necessitated new visual approaches, inspiring artists like Ely Bielutin, Oscar Rabin, Ülo Sooster, and others to experiment with colour, line, composition and other visual elements. This emerging art movement presented greater emotional depth compared to Socialist Realism, favouring abstract forms over natural ones. It celebrated the individual, regardless of their profession or social status, by emphasising universal human qualities.

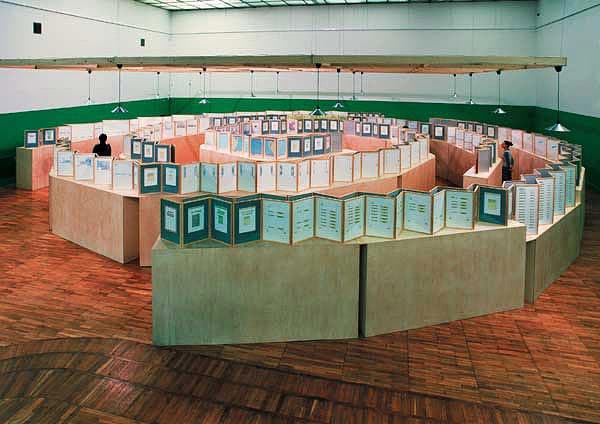

One of the most well-known Non-Conformist artists is Ilya Kabakov, whose cultural dissidence permeates through his paintings, drawings, book-making, installations, theoretical texts, and memoirs. In one series of albums called Ten Characters (1972-75), Kabavok tells the story of a man who attempts to write his autobiography. Along the way realises he has nothing to write, as nothing has ever happened to him. So instead, he creates ten different characters to explain his perception of the world.

Ilya Kabakov's Ten Characters

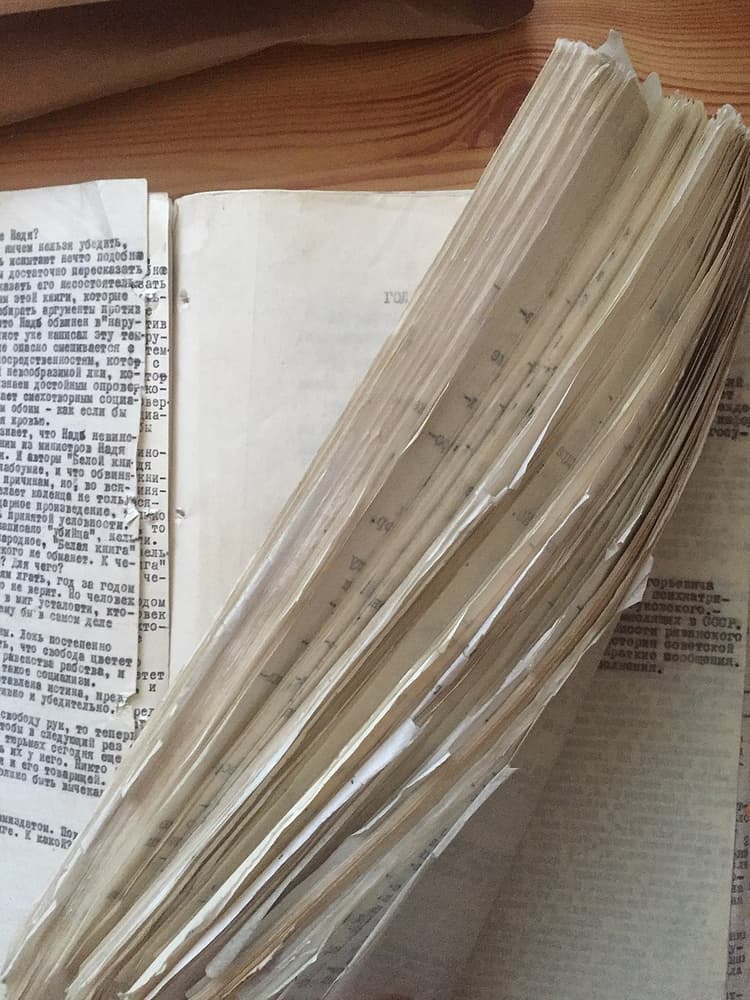

Typewritten Russian samizdat. Moscow.

Following Khrushev, the next predominant Soviet leader was Leonid Brezhnev. He was more conservative and had little sympathy for experimentation in art and literature. Since he did not inhabit the intellectual world, he could not grasp what motivated radicals and dissidents. The Brezhnev leadership quickly revealed its intolerance. In September 1965, writers Andrey Sinyavsky and Yuly Daniel were arrested and later sentenced to seven years and five years hard labour, respectively, for publishing works abroad that slandered the Soviet state.

The might of the state crushed overt cultural dissent, but it stimulated the development of a counterculture. Networks of like-minded individuals wishing to discuss common interests formed and flourished. Works that could not be published in the U.S.S.R. were circulated in typescript (samizdat) or sent abroad for publication (tamizdat).

Samizdat, (from Russian sam, “self,” and izdatelstvo, “publishing”), was literature secretly written, copied and circulated. It was usually critical of practices of the Soviet government. Early samizdat primarily distributed literary works including poetry, unpublished Russian classics, and 20th-century foreign literature. Literature, such as Boris Pasternak's "Doctor Zhivago" and Alexander Solzhenitsyn's "The Gulag Archipelago," fueled its growth. Over time, samizdat evolved to focus more on human rights violations and politics in opposition to the state.

Cover of The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's "The Gulag Archipelago" provides a sobering account of life within Soviet prison labor camps from the late 1910s to the mid-1950s. Through his vivid narrative, Solzhenitsyn exposes theharsh reality of human rights abuses perpetrated by the Soviet Union, countering decades of state propaganda. Central to his argument is the depiction of the Gulag system as a tool of mass violence, exploitation and state-sanctioned murder. Contrary to official claims, the Gulags did not serve any societal benefit nor did they facilitate prisoner rehabilitation. Instead, they served as a means for the government to consolidate power and suppress dissent.

“In keeping silent about evil, in burying it so deep within us that no sign of it appears on the surface, we are implanting it, and it will rise up a thousand fold in the future. When we neither punish nor reproach evildoers, we are not simply protecting their trivial old age, we are thereby ripping the foundations of justice from beneath new generations.”

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918–1956

In his book "The Zone", which recounts his time as a prison guard, Sergei Dovlatov, on the contrary, made a conscious decision not to delve into the most extreme and horrific aspects of camp life. He cited both moral and aesthetic concerns, as well as a desire not to be compared to renowned writers like Shalamov and Solzhenitsyn, known for their stark portrayals of the Gulag's existence. In "The Zone," Dovlatov argued that a Soviet prison camp was a miniature reflection of Soviet society.

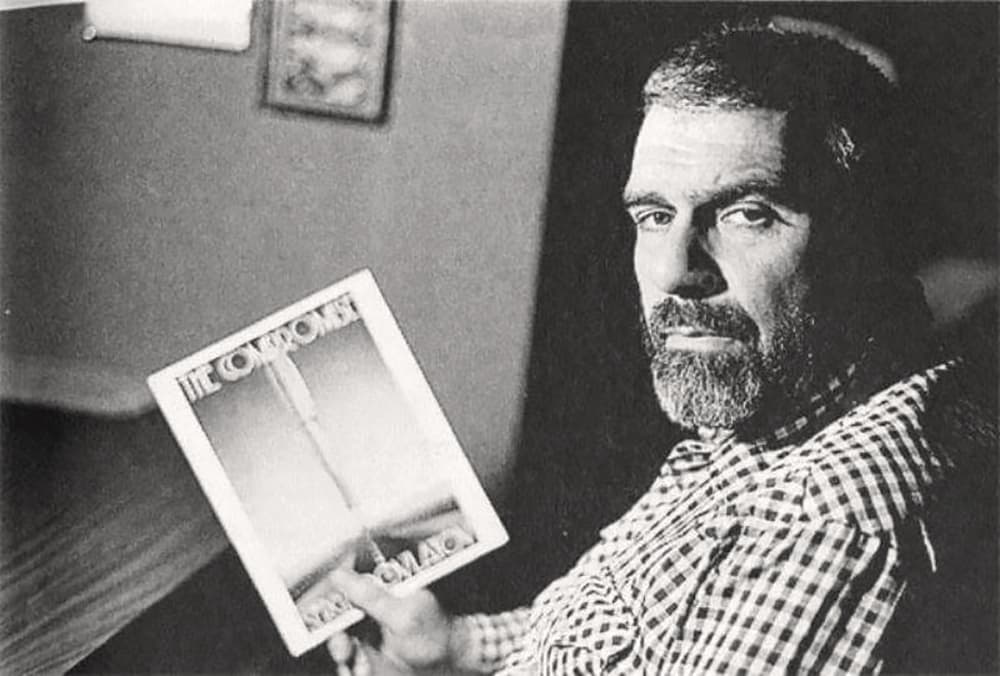

Sergei Dovlatov, author of The Zone and Pushkin Hills

Similarly, in his novel "Pushkin Hills" he playfully depicts the Pushkin estate as a microcosm of Soviet reality, complete with ambitious bureaucrats, loyal supporters of the regime, stubborn peasants, detestable informants and dissenting intellectuals, embodied by the character Boris Alikhanov, who closely resembles Dovlatov himself.

Even though he wrote copious amounts of fiction, he could not get his work published in the Soviet Union. He therefore shared his writings secretly and got them published in other countries, which led to his expulsion from the Union of Soviet Journalists in 1976. Magazines in the West, like "Continent" and "Time and Us," published his stories, but the KGB destroyed the printing plates for his first book.

In 1979, Dovlatov left the Soviet Union with his mother and moved to New York City with his wife and daughter. There, he helped edit a newspaper called The New American. It wasn't until the mid-1980s that Dovlatov finally received recognition as a writer, with his stories appearing in the famous magazine, The New Yorker.

Iosif Brodsky, a poet, translator, essayist, and playwright, faced condemnation and persecution from Soviet authorities – Meanwhile, the Western literary community hailed him as one of the most exceptional poets in the Russian language. Brodsky was deeply rooted in Russian literature and its two-century imperial literary legacy, showing less regard for the Soviet system, which he largely detested and disregarded.

Following his expulsion from his homeland, he relocated to the USA. Over his lifetime, Brodsky authored over two dozen books in Russian and over a dozen in English. His essay compilation, "Less Than One: Selected Essays" (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1986), earned him a National Book Critics Circle Award. Brodsky further achieved the 1987 Nobel Prize in Literature and was designated Poet Laureate of the United States in 1991.

Following the Brezhnev era, Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985. The period of Glasnost’ (openness) and the subsequent collapse of the U.S.S.R. in 1991 was first marked by a dramatic easing of censorship and then to its total abolition. Citizenship was restored to émigré writers, and Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia. Doctor Zhivago and We were published in Russia, as were the works of Nabokov, Solzhenitsyn, Voynovich, and many others.

The divisions between Soviet and émigré and between official and unofficial literature came to an end. Russians experienced the heady feeling that came with absorbing, at great speed, large parts of their literary and artistic traditions that had been suppressed. They additionally gained access to Western cultural movements. A Russian form of postmodernism, fascinated with a pastiche of citations, arose, along with various forms of radical experimentalism. During this period, readers and writers sought to understand the past, both literary and historical, and to comprehend the chaotic, threatening and very different present.

Dieser Artikel wurde noch nicht ins Deutsche übersetzt. Wir suchen nach Freiwilligen, die uns dabei helfen können.

Short biography of the freedom that never happened.

Policy established by Tsar Ivan the Terrible in 16th century involved public executions and ruthless land seizures of aristocrats. How does its legacy remain in current Russian politics?

How Orwell became the Russian Reality

Unsere Medienplattform würde ohne unser internationales Freiwilligenteam nicht existieren. Möchten Sie eine_r davon werden? Hier ist die Liste der derzeit offenen Stellen:

Gibt es eine andere Art wie Sie uns unterstützen möchten? Lassen Sie es uns wissen:

Wir berichten über die aktuellen Probleme Russlands und seiner Menschen, die sich gegen den Krieg und für die Demokratie einsetzen. Wir bemühen uns, unsere Inhalte für das europäische Publikum so zugänglich wie möglich zu machen.

Möchten Sie an den Inhalten von Russen gegen den Krieg mitwirken?

Wir wollen die Menschen aus Russland, die für Frieden und Demokratie stehen, gehört werden lassen. Wir veröffentlichen ihre Geschichten und interviewen sie im Projekt Fragen Sie einen Russen.

Sind Sie eine Person aus Russland oder kennen Sie jemanden, der seine Geschichte erzählen möchte? Bitte kontaktieren Sie uns. Ihre Erfahrungen werden den Menschen helfen zu verstehen, wie Russland funktioniert.

Wir können Ihre Erfahrungen anonym veröffentlichen.

Unser Projekt wird von internationalen Freiwilligen betrieben - kein einziges Mitglied des Teams wird in jeglicher Weise bezahlt. Das Projekt hat jedoch laufende Kosten: Hosting, Domains, Abonnements für kostenpflichtige Online-Dienste (wie Midjourney oder Fillout.com) und Werbung.

Russland hat den Krieg gegen die Ukraine angefangen. Dieser Krieg dauert schon seit 2014 an. Er hat sich seit 24. Februar 2022 nur noch verschärft. Millionen von Ukrainern leiden. Die Schuldigen müssen für ihre Verbrechen zur Rechenschaft gezogen werden.

Das russische Regime versucht, die liberalen Stimmen zum Schweigen zu bringen. Es gibt russische Menschen, die gegen den Krieg sind - und das russische Regime versucht alles, um sie zum Schweigen zu bringen. Wir wollen das verhindern und ihren Stimmen Gehör verschaffen.

**Die russischen liberalen Initiativen sind für die europäische Öffentlichkeit bisweilen schwer zu verstehen. Der rechtliche, soziale und historische Kontext in Russland ist nicht immer klar. Wir wollen Informationen austauschen, Brücken bauen und das liberale Russland mit dem Westen verbinden.

Wir glauben an den Dialog, nicht an die Isolation. Die oppositionellen Kräfte in Russland werden ohne die Unterstützung der demokratischen Welt nichts verändern können. Wir glauben auch, dass der Dialog in beide Richtungen gehen sollte.

Die Wahl liegt bei Ihnen. Wir verstehen die Wut über die Verbrechen Russlands. Es liegt an Ihnen, ob Sie auf das russische Volk hören wollen, das sich dagegen wehrt.