Trade unions in Russia

Among individuals with left-leaning perspectives, there is often a perception that Russia leans leftward, particularly concerning workers' rights. Is this indeed the case?

Freedom of speech faces continuous challenges. In 2022, 533 journalists (a record number) were arrested around the world, that's 13.4% more than the previous year. Even in seemingly free countries in the European Union, the trend can be observed.

In March 2023, the Hungarian media Átlátszó, known for its corruption investigations, was declared a foreign agent and subjected to persecution in pro-government media. One of the country's main independent media, Origo, drastically changed its editorial policy after being acquired by a media conglomerate linked to the family of Hungary's central bank chief.

People gather at the “Free People, Free Media” protest on the Main Square in Krakow, Poland, in December 2021. (Photo credit: Beata Zawrzel/NurPhoto)

In Poland, a state commission is to be established to investigate Russia's influence on the country's internal security. The commission is authorised to investigate the activities of the media, interrogate journalists, initiate criminal cases, and impose a ten-year ineligibility sentence for journalists. The leader of the ruling Law and Justice party, Jarosław Kaczyński, hinted that the commission would target independent media journalists as well. This is not the first such case in Poland: in 2018, Tomasz Piątek, the author of a book about the connections between the previous Polish Minister of Defense Antoni Macierewicz and Russian intelligence, faced threats of imprisonment.

What happens when the state gradually and stealthily takes control of the media, while society lacks the strength to defend freedom of speech? This is a story of how the state uses television to promote its interests, hide corruption, manipulate elections, and even justify aggressive expansionist wars.

According to the research company Mediascope, approximately 63% of Russians turn on their television at least once a day. However, the main audience for TV channels consists of individuals over the age of 54, with 52.5% of TV viewers falling into this category. Russians aged 35-54 make up 29.5% of the total viewership, those aged 18-34 account for 11.5%, and individuals aged 4-17 represent 6.4%.

But this doesn't mean that the younger generation is shielded from propaganda — the ideological influence on children begins as early as the first grade of school through other means.

States can gain control over television through various methods, and the Russian government uses many of them:

Alexei Miller, CEO of Gazprom owning big portion of the Russian TV market

Yelena Masyuk, a journalist abducted and held for 101 days in Chechnya

The Russian government uses all these measures to control the central nationwide television. However, they are also applied to the rest of the TV market. For example, the regional channels are commonly owned by either the members of regional governments or by the big business owners (who often have ties to the state). All publicly available regional and municipal channels are financed by their regional governments.

The control measures extend their reach beyond the central TV, affecting also the pay TV—digital and cable. Since the operators are the same companies linked to Putin—such as the sanctioned Rostelecom—they also follow the pro-government agenda. For example, in 2014, the oppositional channel TV Rain disappeared from the package of the satellite operator Tricolor TV.

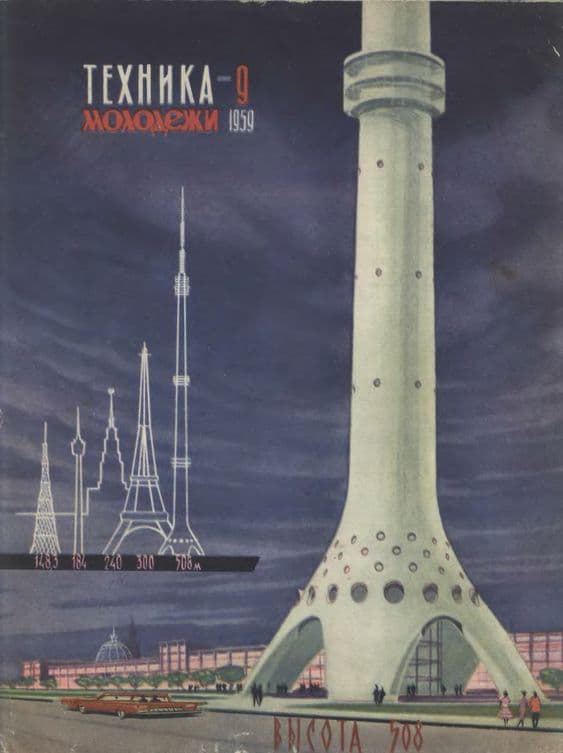

Ostankino TV tower. Cover of "Tekhnika Molodezhi" (Technology for Youth) Soviet poster, 1959

In Russia, there is a strong tradition of state control over television, which has its roots in the Soviet Union. Television broadcasting in what is now Russia began in 1931 as an initially state-owned instrument of mass communication. During the Soviet era, all television channels in the country were state-owned. They were tightly censored, overseen by the State Committee of the USSR for Television and Radio Broadcasting.

"The bright light of Science showed there is no god", 1960s

Criticism of the government was strictly prohibited, and television exclusively portrayed the successes of the USSR and the failures of "Western imperialist" countries. Many events were simply not reported. For instance, Soviet television did not cover the events in Novocherkassk in 1962 when 24 protesters were killed during the suppression of a demonstration. The Soviet media also began reporting on the Chernobyl nuclear disaster only 1.5-2 days after the reactor explosion, by which time a vast area of the country was already contaminated with radiation.

Over 60 years, both industry workers and the audience became accustomed to the state control of TV, where television was the official voice of the state and a trusted source. Although the situation changed after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, television remains the most trusted information source in Russia even in 2023.

"Do not leave the TV on unattended", 1980s

After the USSR collapse, state television companies, VGTRK and Ostankino, emerged from the Committee for Television and Radio Broadcasting. These television companies were in a deep financial crisis, and private investors were brought in to support their operations.

The 1990s marked a brief period in Russia's history when the state control on television was reduced. While a degree of state influence over television still remained, compared to the Soviet era, it was a glimpse of freedom. For the first time in Russian TV history, open criticism of both Soviet and Russian authorities began.

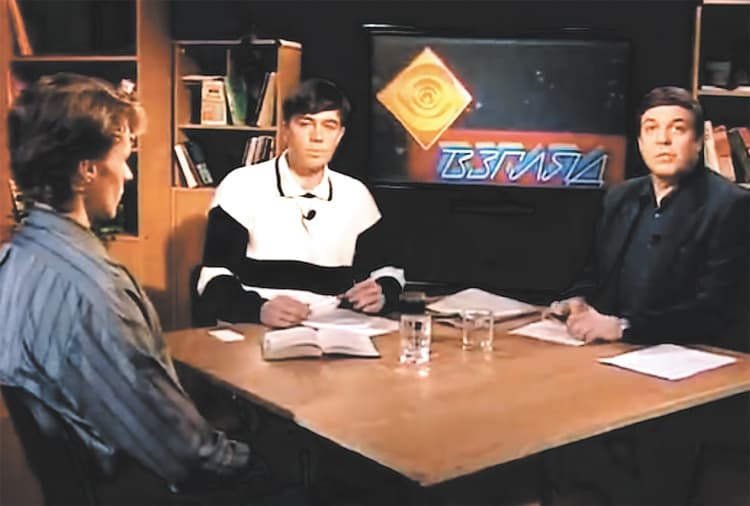

This era saw the introduction of programmes such as:

Outlook, 1987 – 2001

Before and After Midnight, 1987 – 1991

Vox Populi, 1999 – 2001

Theme, 1992 – 2000

Yelena Khanga, moderator of About This

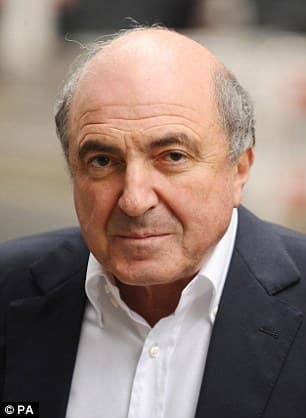

Boris Berezovsky, a Russian oligarch

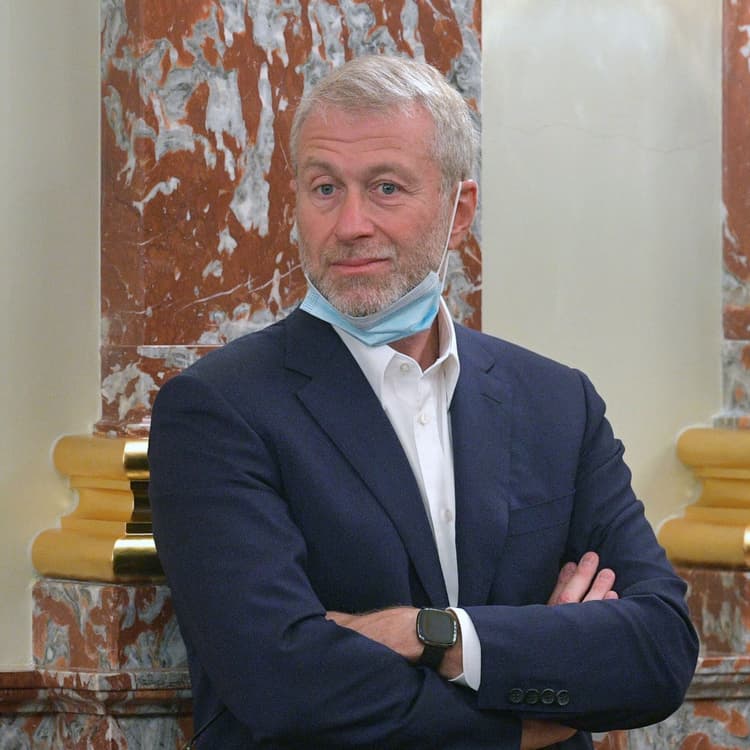

The first and most prominent channel, ORT, was half-funded by the state and 'half-funded by a famous Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky. Under the Soviet Union, Berezovsky had been the director of one of the major Soviet automobile plants, and in the 1990s, he co-founded the oil company Sibneft along with another famous Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich. The second most popular channel, RTR, came under the control of the state and was led by former Soviet journalists and media managers.

Alongside ORT and RTR, the third most popular channel in the country was NTV. In 1993, journalists from ORT, with financial support from businessman Vladimir Gusinsky, established the television company NTV. Gusinsky had ventured into business during the Perestroika era and, by 1992, he owned the Joint Stock Company Most, which dealt with real estate, finance, and later, media.

Roman Abramovich, a Russian oligarch

In the 1990s, Russia saw the emergence of numerous other popular private TV channels that were also owned by the big business:

Vladimir Potanin, a Russian oligarch

This led to oligarchs having significant control over the agenda of television channels, as demonstrated by the 1997 incident involving the company Svyazinvest. At that time, the interests of oligarchs Vladimir Gusinsky and Vladimir Potanin collided in an auction for the right to control a large block of shares of the telecommunications company Svyazinvest. Gusinsky had hoped to win the auction, but Potanin emerged as the victor. Gusinsky accused the auction's organiser, then-Finance Minister Anatoly Chubais, of conspiring with Potanin and initiated an information war against them using media outlets under his control.

These events had to have an effect on the trust of the people in private TV. It turned out that independent television channels were not as independent as they seemed, capable of presenting events in a way that favoured their owners and promoting the interests of the oligarchs. This can be seen as one of the things that laid the groundwork for the subsequent takeover of television by the state.

In January 2000, acting President Vladimir Putin appointed his trusted ally, Oleg Dobrodeev, as the Chairman of VGTRK. From this moment on, Putin began swiftly taking control of Russian television.

In September 2000, after the broadcast of a critical story by Sergey Dorenko about Putin's behaviour during the Kursk submarine disaster, Boris Berezovsky, under pressure from the Kremlin, sold his shares in ORT (Channel One) to Roman Abramovich. The channel's editorial policy underwent a sharp change, and such stories never appeared on it again.

On May 11, 2000, just four days after Putin assumed the presidency, raids began at Vladimir Gusinsky's Media-Most holding office. On June 13, Gusinsky himself was arrested. A month later, in exchange for his freedom, he signed an agreement to transfer one of the country's most popular television channels, NTV, to Gazprom-Media.

Vladimir Kara-Murza, one of the protesters against NTV takeover, was recently sentenced for 25 years in prison for "treason"

In April 2001, there was a takeover of NTV, a channel that had actively criticised the actions of Russian military forces in Chechnya during those years. At a shareholders' meeting of Gazprom-Media, there was a complete change in the channel's management. Several leading NTV journalists refused to accept this decision, including Vladimir Kara-Murza, who was later sentenced to 25 years in prison on various charges, including “discrediting” the military and treason.

The authorities justified the takeover of NTV by citing the channel's financial problems, arguing that Gazprom had to take control to save the company. However, Kara-Murza and his colleagues claimed that financial pressure was being exerted by the team that came to power in 2000 under Vladimir Putin, which was often criticised by NTV. The channel was not actually running at a loss: in 2000, the media company's income was $14 million, of which $4 million were paid in taxes.

For several days, journalists did not allow representatives of Gazprom-Media into the NTV studio. Protests in support of the channel team were held, and the channel's broadcasting was temporarily switched to round-the-clock mode. However, this did not help. Some employees supported the new management, and Gazprom representatives replaced the security at the NTV office, invalidating the old passcards, allowing in only those employees who recognised the new leadership.

The takeover of NTV was presented as if nothing much had changed—just one set of managers replaced another. Initially, the channel's editorial policy did not change significantly: for the first couple of years, it continued to criticise the government almost "by inertia." Nevertheless, the new editor-in-chief of NTV, Vladimir Kulistikov, gradually changed the channel's content. Instead of socio-political programmes, numerous police series and shows with "yellow" crime chronicles appeared.

To a large extent, NTV's image was tarnished by its oligarchic background: everyone remembered the television wars against the government in 1997 and the scandal with Svyazinvest. Moreover, in his speeches, Putin also framed the oligarch control over TV as problematic. Therefore, the state's takeover of television could be perceived as a way to rid it of oligarchic control.

By the spring of 2001, all three major channels in the country—Channel One, VGTRK (known as Russia 1 nowadays), and NTV—were taken over by Putin's administration. Competitive coverage of current events virtually disappeared from Russian TV. Journalists who did not support the takeover of NTV moved to TV-6, but the channel was also closed a few years later. However, at that time, private channels still existed.

In the 2000s, the takeover of television channels continued. A key player in this was the Gazprom-Media holding. Although it is formally a private company, in reality, as the largest producer and exporter of gas in Russia, Gazprom serves as the "cash cow" for the state. 50% of Gazprom's shares belong to the Russian government, and another 25% of top shareholders include people like Prime Minister Alexander Novak and Agriculture Minister Dmitry Patrushev.

Gazprom is the largest company in the Russian market. Among its subsidiaries is the media holding Gazprom-Media. In the 2000s, it was Gazprom-Media that actively began acquiring independent television channels. Today, it owns the most popular Russian channels such as Match TV, TV-3, Pyatnitsa, and TNT.

Instead of openly taking ownership of these channels, the state indirectly controls them through companies owned by Putin's friends. Another example is STS Media. In 2014, the largest shareholders of STS Media were the Swedish company Modern Times Group and the Cypriot company Telcrest. However, the following year, STS Media was bought out by a mining and metallurgical holding owned by Alisher Usmanov, another friend of Putin who earns from the sale of natural resources and has faced allegations of corruption. Today, STS Media owns other popular channels like STS, Domashniy, and Che.

No matter which channel you look at, most of them are owned either by the state or by oligarchs who earn money by trading Russia's natural resources. The Fifth Channel and REN TV, as well as a portion of Channel One and STS Media, belong to the National Media Group, a company owned by Alexey Mordashov, yet another mining and metallurgical magnate and a figure on the EU and U.S. sanctions lists.

The omnipresence of the state in the media doesn’t leave much room for independent television. Nevertheless, even under such conditions, the state did not completely eliminate independent Russian TV, although its examples are rare and far between.

Natalia Sindeeva, founder of TV Rain

Until 2022, TV Rain operated in Russia—an independent channel founded by media manager Natalia Sindeeva and her husband, investor Alexander Vinokurov. The channel is not dependent on sponsors and receives most of its revenue from advertising and paid subscriptions. TV Rain is known for its opposition-oriented news, analytical, and discussion programmes. The channel openly discusses topics like war, corruption, protest movements, repression, and other pressing issues. Today, TV Rain continues to broadcast from the Netherlands.

Today, all Russian-language channels that are not dependent on the Russian government broadcast from other countries because Russian law prohibits them from operating within Russia, especially as foreign agents. For example, the Current Time studio is located in Prague, and OstWest is in Berlin.

Alternative news and analytics, however, are not the only form of resistance or attempt to exist outside of state control. Alternative culture (films, music, comedy) has sought refuge in the space of entertainment TV channels and cable TV, where it was able to exist relatively undisturbed for some time, while the control around the central federal news channels tightened.

Music channels, such as MTV Russia or A-ONE, were often the source of Western culture and liberal values

For example, MTV Russia that started broadcasting in 1998, seven years after the fall of the USSR, has brought in the Western culture in the form of music and shows, exposing viewers to a set of values alternative to the one inherited from the Soviet Union. It had a considerably more open approach to sexuality, LGBT representation, and oppositional shows about Russian politics like Gosdep (which was closed in 2012, allegedly because of the planned appearance of the opposition leader Alexei Navalny). In 2013, it stopped broadcasting and was relaunched as a satellite channel, and in 2022, after the start of the Russian invasion in Ukraine, Paramount (which owns the MTV brand) has suspended its activities in Russia.

Another example was A-ONE — a music channel that streamed alternative music, including Russian openly oppositional music and foreign alternative music that arguably went against “traditional Russian values” (e.g. punk).

For example, one of the big hits in the late 2000s on this channel was a song “The State” (original: “Gosudarstvo”) by the Russian band Lumen with lyrics:

Pay your taxes and sleep easy, but wars are funded with this money... It’s supposed to be a democracy here, but really it's a kingdom. I love my country so much but I hate the state.

Currently, this song has been legally proclaimed to be extremist.

In 2011, the channel went under new management and its format was changed. In 2016, it was bought by Gazprom Media Holding and closed (rebranded as a completely different channel).

Yet another example is the 2x2 channel. Since its launch in 1989, its content has been mostly of the Western culture—MTV shows (before the official launch of MTV Russia), BBC News, Discovery channel programmes. Since 2007, they have started showing mostly children and adult animation (such as Adult Swim shows). Following a series of scandals, including the depiction of Vladimir Putin as a greedy and desperate leader in the show South Park, the channel started practising self-censorship. Consequently, in 2014, the channel was acquired by Gazprom-Media.

Apart from the entertainment channels, another space where control of the state was not as strict (at least for a certain period of time) was cable and satellite TV. Crucially, having access to cable or satellite television means access not only to domestic non-broadcast channels, but also to a great number of channels operating from abroad, which are harder to bring under state control. However, most large cable television operators (such as Rostelecom, whose main share is owned by the Russian government) can be controlled by the state, which means that the channels disapproved by the state can be removed from the menu. Moreover, the non-broadcast channels are still subject to Russian law, such as the ban on advertising on cable TV, which can drive channels out of the Russian market, or censorship laws (such as the “LGBT propaganda” law or the law against “discrediting the military”, which can be used to block channels in Russia entirely.

Euronews, launched in 2001, the channel has been repeatedly criticised by the Russian authorities. In March 2022, access to the Euronews channels and websites in Russia were restricted as, claimed by Roskomnadzor, it:

[Euronews] have systematically posted unreliable and publicly significant information on a special military operation being carried out by the Russian Armed Forces, as well as information containing calls for people to participate in mass (public) events held in violation of the regulations established in the Russian Federation.

Roskomandzor, Russian Federal Service for Supervision of Communications

Later, the channel’s frequency was given to Solovyov Live hosted by Vladimir Solovyov, a famous Russian propagandist.

The BBC's presence in Russia faced a series of challenges that ultimately led to its cessation. In August 2021, diplomatic tensions rose when the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs refused to extend the visa of the BBC's Moscow correspondent, Sarah Rainsford, in response to the UK's non-renewal of accreditation for a Russian journalist. However, the most significant blow came in 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine. As stated officially:

The BBC had temporarily suspended its journalists' work in Russia, in response to a new law which threatens to jail anyone Russia deems to have spread "fake" news on the armed forces.

BBC's statement

On March 3, the BBC's website was blocked in Russia.

The German news outlet faced no issues in Russia until the late 2010s. The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs raised concerns over a tweet featuring an interview with Zhanna Nemtsova where it was mentioned that Oleg Sentsov had called Vladimir Putin a "bloody dwarf". In March 2022, Russian authorities labelled Deutsche Welle a "foreign agent", citing concerns over its activities. DW relocated to Riga and ceased its operations in Russia ever since.

At first they stopped broadcasting in Russia from January 2015 to April 2015 due to legislative changes in Russian media regulations, specifically related to advertising restrictions on paid channels. In 2022, the owner of CNN decided to suspend their operations in Russia, following a similar move by other channels. This decision came after the Russian president signed a law imposing penalties for spreading "fake information about the Russian armed forces", with potential fines and prison sentences for offenders.

Vox Populi, Rush Hour, Results, Puppets, and other programmes on ORT and NTV that became symbols of independent television in the 1990s were shut down. On Channel One, Russia 1, NTV, and soon on other channels, discussions of views different from the official state position permanently ceased. Television, once a platform for discussion and coverage of current events, turned into a propaganda megaphone. In addition to the old channels like Channel One and Rossiya 24, new propaganda channels have appeared—for example, Russia Today (RT). It is aimed not only at the Russian, but also at the foreign audience.

In the 1990s, the television openly:

Today, the hosts of the country's main channels:

Having gained control over television, the state obtained the ability to:

YouTube blocked the following channels:

Also propagandists:

Sometimes the propaganda machine malfunctions. For example, right after the start of the war in 2022, a young woman who worked as an editor for Channel One, stormed into the live broadcast of news with a poster. The poster read:

"No war! Stop the war, don't believe the propaganda, they're lying to you."

Tento článek ještě nebyl přeložen do češtiny. Hledáme dobrovolníky kteří by nám s tím pomohli.

Among individuals with left-leaning perspectives, there is often a perception that Russia leans leftward, particularly concerning workers' rights. Is this indeed the case?

How Orwell became the Russian Reality

Conspiracy theories and bogus science: Russia uses this in criminal cases, propaganda and justification of war. What are the most famous cases of this and how does it work?

Naše mediální platforma by neexistovala bez našeho mezinárodního týmu dobrovolníků. Chcete se stát jedním/jednou z nich? Zde je seznam aktuálně otevřených pozic:

Je nějaká další oblast ve které byste nám rádi pomohli? Dejte nám vědět:

Mluvíme o současných problémech Ruska a jeho obyvatel, o boji proti válce a za demokracii. Snažíme se, aby byl náš obsah co nejpřístupnější evropskému publiku.

Chcete spolupracovat na obsahu, který vytvořili ruští autoři stojící proti válce?

Chceme, aby lidé v Rusku, kteří se zasazují o mír a demokracii, byli slyšet. Zveřejňujeme jejich příběhy a děláme s nimi rozhovory v rámci projektu Ptej se Rusů.

Jste ruský občan nebo znáte někoho, kdo by se chtěl podělit o svůj příběh? Obraťte se na nás. Vaše zkušenosti pomohou lidem pochopit, jak Rusko funguje.

Vaše zkušenosti můžeme zveřejnit anonymně.

Náš projekt vedou dobrovolníci z celého světa - žádný člen týmu není nijak placen. Projekt však má provozní náklady: hosting, domény, předplatné placených online služeb (např. Midjourney nebo Fillout.com) a reklamu.

Číslo našeho transparentního bankovního účtu je 2702660360/2010, založená je u Fio Banky (Česká republika). Můžete nám buď poslat peníze přímo na něj, nebo nascanovat jeden z QR kódů níže ve vaší bankovní aplikaci:

Poznámka: QR kódy fungují pouze pokud je nascanujete přímo z vaší bankovní aplikace.

Rusko zahájilo válku proti Ukrajině. Tato válka probíhá od roku 2014. 24. února 2022 se pouze zintenzivněla. Miliony Ukrajinců trpí. Ruští činitelé kteří válku zavinili, musí být za své zločiny postaveni před soud.

Ruský režim se snaží umlčet pro-demokratickou část společnosti. Ruští lidé, kteří jsou proti válce, existují - a ruský režim se je snaží ze všech sil umlčet. Chceme tomu zabránit a jejich hlasy nechat zaznít.

Spojení je klíčové. Ruské pro-demokratické iniciativy jsou pro evropskou veřejnost často těžko čitelné. Právní, sociální a historické souvislosti Ruska nejsou vždy jasné. Chceme sdílet informace, budovat mosty a propojovat pro-demokratickou část Ruska se Západem.

Věříme v dialog, ne v izolaci. Opoziční síly v Rusku nebudou schopny cokoli změnit bez podpory demokratického světa. Věříme také, že dialog by měl probíhat oběma směry.

Výběr je na vás. Chápeme hněv vůči ruským zločinům. Jen na vás záleží, zda chcete naslouchat ruskému lidu, který se proti tomu staví.